women's

suffrage movement

Beginning in the mid-1800s, several generations of woman suffrage supporters lectured, wrote, marched, lobbied, and practiced civil disobedience to achieve what many Americans considered the most radical change in the Constitution to date—guaranteeing women the right to vote. Suffrage had already been extended to men, regardless of their race, motivating women across the nation to wonder why they didn't have a voice in the politics and developments happening in their own country. Little did they know, the strength in their voices and the changes they fought for in their own country would quickly become an international movement.

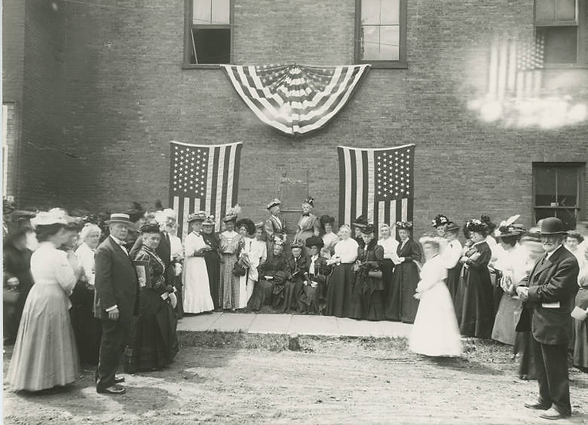

"Celebration of the 60th anniversary of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention," Seneca Falls Historical Society, New York Heritage

Seneca Falls Convention

The first women's rights convention was organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a number of Quaker women in Seneca Falls, New York. They aimed to open discussion among the roughly 300 attendees concerning the rights and conditions of women in society, religion, and politics.

what was the Seneca Falls Convention?

The Seneca Falls Convention, originally called the Woman’s Rights Convention, was a meeting that worked for women's rights, including social, civil, and religious freedoms. It was held on July 19–20, 1848, at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York. Even though the event wasn’t widely advertised, about 300 people, mostly from the local area, attended. On the first day, only women could attend, but on the second day, men were allowed to join in. One of the organizers, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, started the meeting with a speech explaining the purpose and goals of the convention:

“We are assembled to protest against a form of government, existing without the consent of the governed—to declare our right to be free as man is free, to be represented in the government which we are taxed to support, to have such disgraceful laws as give man the power to chastise and imprison his wife, to take the wages which she earns, the property which she inherits, and, in case of separation, the children of her love.”

The convention then discussed 11 resolutions about women's rights. All of them were approved unanimously, except for the ninth resolution, which called for women to have the right to vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass gave powerful speeches in support of it, and after a heated debate, it was finally passed—though just barely.

who organized the Seneca Falls Convention?

"International gathering of women's suffrage advocates in Washington, D.C., 1888," Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The Seneca Falls Convention was organized by five women who were also deeply involved in the fight to end slavery and fight racial discrimination. These women were:

-

Elizabeth Cady Stanton – A leader in the women's rights movement, Stanton was a key organizer of the convention. She became interested in women's rights after talking with her father, a law professor, and his students. She studied at Troy Female Seminary and worked to change laws about women’s property rights in the early 1840s.

-

Lucretia Mott – A Quaker preacher from Philadelphia, Mott was known for her work against slavery, for women’s rights, and for religious reforms.

-

Mary M’Clintock – The daughter of Quaker activists who fought against slavery, supported women’s rights, and promoted temperance (the movement to limit alcohol use). In 1833, M’Clintock and Mott helped create the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. At the Seneca Falls Convention, M’Clintock served as the secretary.

-

Martha Coffin Wright – Lucretia Mott’s sister, who was also a strong supporter of women’s rights and an abolitionist. She ran a station on the Underground Railroad from her home in Auburn, New York.

-

Jane Hunt – A Quaker activist and a member of M’Clintock’s extended family through marriage.

Stanton and Mott first met in 1840 at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where women were not allowed to participate because of their gender. This experience inspired them to plan a women’s rights convention.

did you know?

Susan B. Anthony, one of the most famous women’s rights activists, did not attend the Seneca Falls Convention. She would meet Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1851, and the two would spend the next 50 years fighting for women’s rights together, including co-founding the American Equal Rights Association.

By the 1830s, women’s rights activists in the U.S. were already pushing for the right to speak out about political and moral issues. In New York, where Stanton lived, legal reformers were fighting to change laws that didn’t allow married women to own property. By 1848, the fight for women’s equality was a hotly debated issue.

what was the outcome of the Seneca Falls Convention?

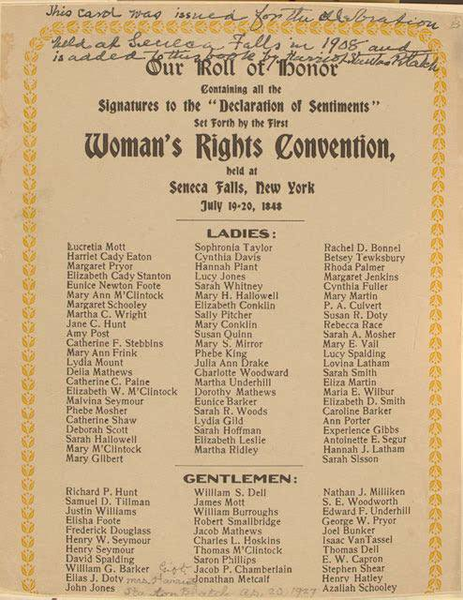

The Seneca Falls Convention produced the "Declaration of Sentiments", a document that demands equal rights. The Declaration of Sentiments starts by saying that all men and women are equal and have the same basic rights, like the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It explains that women are being treated unfairly by both the government and the society they live in. The document then lists 16 ways women are oppressed, such as not being allowed to vote, not being able to participate in or represent the government, not having property rights in marriage, and being treated unfairly in divorce laws. It also highlights the lack of equal opportunities for women in education and jobs. The document calls for women to be treated as full citizens of the United States and to have the same rights and freedoms as men.

Overall, the meeting launched the women's suffrage movement. Unfortunately, the right to vote would not be given to women until more than seven decades later.

"Declaration of Sentiments," Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

'Women’s Suffrage Delegation on the steps of the State Capitol with Governor Charles Brough, 1917," Arkansas State Archives

the right to vote

Many of the attendees to the Seneca Falls Convention were also abolitionists whose goals included universal suffrage – the right to vote for all adults. In 1870 this goal was partially realized when the 15th amendment to the Constitution, granting black men the right to vote, was ratified. Woman suffragists' vehement disagreement over supporting the 15th Amendment, however, resulted in a "schism" that split the women's suffrage movement into two new suffrage organizations that focused on different strategies to win women voting rights.

the NWSA and the AWSA

In May 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) because they opposed the 15th Amendment, which gave voting rights to men but not women. The NWSA sent petitions to Congress asking for voting rights for women and for women to be allowed to speak in Congress.

The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was also formed in 1869 by Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. The AWSA supported the 15th Amendment and focused on getting women the vote in state and local elections, believing that small victories would lead to larger change. In 1890, the NWSA and AWSA merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which became the largest suffrage organization in the U.S. and led the fight for women’s voting rights until the 19th Amendment passed in 1920. Stanton became president, Anthony became vice president, and Stone became chair.

"A group of Women's Suffrage activists march in a parade carrying a banner reading 'I Wish Ma Could Vote' circa 1913," Getty Images

Susan B. Anthony used another strategy in 1872 by registering and voting in an election in Rochester, NY. She was arrested and fined $100 for voting illegally, but she refused to pay the fine and petitioned Congress to have it removed.

Frederick Douglass, an important leader in the abolitionist movement, also supported women's suffrage. He attended the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 and wrote in his newspaper, The North Star, that women should have the right to vote. Many African American women also joined the suffrage movement, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell, and Adella Hunt Logan.

Top, left to right: "Suffragettes advertising women's rights at The Cooper Union, a tuition-free school which prided itself on a lack of discrimination, New York City, circa 1859-1900," Getty Images; "Suffrage and Sedition," Virginia Commonwealth University. Bottom: "Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony," Historical Photos of Women's Stories

passing the amendment

In the early 1900s, suffragists held large parades to raise awareness, like the march in Washington, D.C., in 1913, which had over 5,000 participants. During World War I, suffragists used protests to pressure President Woodrow Wilson to support the right to vote for women. One group, the National Woman's Party (NWP), even staged the first-ever White House picket in 1917, where they silently demonstrated for women’s rights. Many of them were arrested and treated harshly in jail (force-fed, beaten, emotional abuse), but this helped gain more sympathy for their cause.

By 1917, New York passed women’s suffrage, and Wilson changed his stance to support a constitutional amendment. After years of struggle, the 19th Amendment was passed by Congress in 1919 and sent to the states for ratification. Tennessee became the crucial 36th state to ratify the amendment on August 18, 1920, after a last-minute change of vote by a young legislator at his mother’s urging. This led to the final adoption of the amendment, giving women the right to vote. While the fight for equality continued for African American and other minority women, this was a huge victory for the women’s suffrage movement.

"1913 Women's Suffrage Procession," National Park Service

women's marches

Women’s marches were (and still are!) crucial expressions of solidarity, empowerment, and advocacy for gender equality. They provided a platform for women to voice their concerns, challenge systemic injustices, and demand equal rights and opportunities. These marches helped to inspire collective action and create a sense of community. By coming together, women amplified their voices, showing that progress is a collective effort, and they helped shift societal attitudes toward greater gender justice and inclusion.

While not all of the following marches were directly concerning women's suffrage, they were all spearheaded by strong women who showed the nation that women were just as powerful as men. The following marches occurred before the passing of the 19th Amendment.

Mother's Day March, 1868

Before the Civil War, public healthcare for women and children in the United States, especially for prenatal and postnatal care, was extremely limited. The country was also deeply divided, with opposing social and political views causing tension between people who were once neighbors. Ann Marie Reeves Jarvis, a wife and mother from what is now West Virginia, experienced these challenges firsthand. Like many women of the 1850s, she gave birth to twelve children, but only four survived childhood, largely due to deadly diseases. Concerned about the health of children, Jarvis took action and founded several "Mother's Day Work Clubs" to help mothers support each other and address the poor health conditions contributing to high child mortality rates. These clubs provided medicine, nursing care, and resources for families in need.

When the Civil War began, Ann Jarvis urged the members of her clubs to embrace peace and goodwill, despite the country's growing divisions. As a peacemaker, she encouraged women to rise above the conflict and hatred caused by the war. Jarvis inspired the women in her clubs to care for both Union and Confederate soldiers, offering medical aid to all and saving many lives in the process. Her efforts showed that kindness and compassion could bridge even the deepest divides.

After the war, Jarvis continued her work to heal the country. In 1868, she created “Mother’s Friendship Day,” an event designed to bring together families torn apart by social and political conflict. Ann believed that by honoring the love and respect people have for their mothers, they could begin to rebuild relationships and find common ground. The event was a success, drawing people from both sides of the war who came together in a spirit of reconciliation. By the end of the day, many families had reconciled, embracing each other in tears. Jarvis’ mission was clear: “To make us better children by getting closer to the hearts of our good mothers. To brighten the lives of good mothers.”

The March of the Mill Children, 1903

"We want to go to school, not the mines!"

At the turn of the twentieth century, child labor was widespread in the United States, particularly among poor and working-class families. The 1900 census revealed that 26% of boys and 10% of girls aged 10 to 15 were working, with even higher rates in some states. For instance, in Alabama, 60% of young boys were employed. There were no national laws regulating child labor at the time, and many children worked in dangerous conditions, often under the threat of serious injury or death. Most children worked in factories and mines, where they operated heavy machinery in textile mills or toiled in hazardous underground conditions, often barefoot and dressed in rags.

In 1903, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones, an Irish-born socialist and labor organizer, visited Kensington, a neighborhood in Philadelphia, where textile workers were striking for better wages and shorter work hours. She discovered that among the striking workers, around 10,000 were children—some as young as seven. Though Pennsylvania law prohibited children under the age of 12 from working, the law was poorly enforced, and many parents lied about their children's ages out of financial necessity.

In July 1903, Mother Jones led a three-week march from Philadelphia to New York City, with nearly 200 participants, including many children, to raise awareness about child labor and demand reform. Along the 92-mile journey, the marchers held rallies, raised funds, and tried unsuccessfully to meet with President Theodore Roosevelt. While the march didn’t lead to immediate changes in child labor laws, it did bring national attention to the issue. In 1904, the National Child Labor Committee was formed, and after years of campaigning, Pennsylvania passed a new child labor law in 1915, raising the minimum working age to 14. However, it wasn’t until 1938, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, that the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, setting national standards for child labor and protecting young workers across the country.

"Mother Jones and the March of the Mill Children," Kathleen McLane

Women's Christian Temperance March on Washington, 1913

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was founded in Cleveland, Ohio, in November 1874. It grew out of a movement called the "Women’s Crusade," which was a protest against alcohol in the winter of 1873-1874. During the 1800s, many women became involved in social reform movements, and the WCTU’s main goal was to reduce the negative impact of alcohol on families and society. After the Civil War, alcohol was a major problem, causing poverty and domestic violence. At the time, women didn’t have many rights—like the right to vote or control their property—and were often the ones leading the charge against alcohol, hoping to make their homes safer.

In 1879, Frances Willard became the president of the WCTU and worked to promote total abstinence from alcohol. She also pushed for many other reforms, like women’s right to vote, equal pay for women, shelters for abused women and children, and better laws around marriage and divorce. On December 10, 1913, one of the biggest demonstrations for prohibition took place in Washington, D.C. About 1,000 women from the WCTU, along with 1,000 men from the Anti-Saloon League, marched silently toward the U.S. Capitol. Thousands of bystanders joined the march, making it a huge event. They met with lawmakers, including Senator Morris Sheppard and Representative Richmond P. Hobson, and handed over petitions asking for a new law to make alcohol illegal. Later that day, Sheppard introduced the proposal for a constitutional amendment to ban alcohol, which eventually helped lead to Prohibition in the United States.

Top: "Frances Willard," Britannica; Bottom: "Day Two: A War of Mothers and Daughters," MSNBC

Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Procession, 1911

On March 25, 1911, a devastating fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City, located in the upper floors of the Asch Building in Greenwich Village. The fire quickly spread, trapping workers inside. A total of 146 people lost their lives in the tragedy, most of them young immigrant women and girls, with some men among the victims. Many of the workers died from smoke inhalation, while others jumped from the windows in a desperate attempt to escape the flames, falling to their deaths on the sidewalk below. The fire began in a scrap bin, though the exact cause was never determined. The situation was made worse by the fact that the factory doors were locked to prevent theft, and the building only had one elevator that was fully working. The fire escape, which many workers tried to use, collapsed under the weight of those fleeing the flames, leading to even more deaths.

The tragedy shocked the nation and highlighted the dangerous and unsafe working conditions in factories. In response, 400,000 people attended a funeral procession on April 2, 1911, to honor the victims. Among those who marched in the procession were 120,000 men, women, and children, including the families of seven victims who could not be identified. The event drew attention to the need for reform in working conditions. On the Sunday after the fire, a meeting was held at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, where activist Rose Schneiderman, a leader of the Shirtwaist Makers Union, delivered an emotional speech about the poor working conditions that led to the tragedy. Schneiderman’s speech urged people to understand the importance of improving labor laws and to fight for the safety and rights of workers. The meeting, along with the work of the New York Factory Investigative Commission, led to the passing of 36 new labor laws, including those focused on fire safety and better working conditions for factory workers. This tragedy helped pave the way for reforms that improved the lives of many workers in New York and across the country.

One person deeply moved by the fire was Frances Perkins, the head of the New York Consumers League, who witnessed the event firsthand. The fire changed her life, and she left her position at the Consumers League to become the Executive Secretary for the Committee on Safety for the City of New York. In this role, she worked to improve the safety of workers, especially in factories. Later, Perkins was appointed the U.S. Secretary of Labor under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, where she worked to create laws that protected workers across the country. The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was a turning point in labor history and is remembered as one of the most tragic events in New York City’s history. It led to sweeping reforms that changed how factories operated and put pressure on lawmakers to take action on worker safety. It wasn’t until decades later, in the 1970s, under President Richard Nixon, that the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) was passed to ensure safer working conditions in industries nationwide.

Women's Suffrage Procession, 1913

The Woman Suffrage Procession of 1913 was a landmark event in the fight for women’s right to vote in the United States. It was the first large-scale suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., and it was organized by Alice Paul and the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The parade was planned to take place on March 3, 1913, the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, with the goal of protesting women’s exclusion from the political process. Over 5,000 women marched from the U.S. Capitol down Pennsylvania Avenue toward the Treasury Building, demonstrating their demand for voting rights. The parade included floats, bands, and marchers dressed in white to symbolize purity and commitment to the cause.

As the marchers made their way through the streets of Washington, they were met with both support and hostility. Many onlookers, including some men, attacked the women—shoving, tripping, and yelling insults. Police, who were supposed to protect the marchers, stood by and did nothing to stop the violence. By the end of the day, more than 100 women had been hospitalized for injuries, but the suffragists refused to stop or give up. They finished the parade, sending a powerful message that they would not be intimidated. This brave show of strength caught the attention of the media, and the news coverage of the march led to widespread support for the suffrage movement. The violence they faced sparked congressional hearings on the treatment of women, and historians later credited the 1913 march with giving the suffrage movement renewed energy and determination.

One of the most iconic images of the parade was of Inez Milholland, a prominent suffragist and activist, who led the march on a white horse. Milholland was a powerful speaker and a major advocate for women’s rights. She traveled across the country giving speeches in support of women’s suffrage, and she became a symbol of the movement’s strength and resolve. Tragically, Milholland died at the age of 30 after collapsing during a speech in Los Angeles. Her last public words were “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” Milholland’s death made her a martyr for the suffrage movement, and her legacy continued to inspire generations of women who fought for their right to vote.

The 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession was a key moment in the long struggle for women's rights in the United States. It was a turning point that brought the issue of suffrage into the national spotlight and showed that women were willing to fight for their rights, no matter the obstacles. The march helped build momentum for the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which was finally ratified in 1920, granting women the right to vote. The 1913 parade remains a symbol of the courage, determination, and activism of women who fought for equality and justice.

Silent Parade, 1917

On July 28, 1917, around 10,000 people gathered for the Silent Parade in New York City, organized by W.E.B. Du Bois and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This was the first major protest rally against lynching, race riots, and the violence African Americans were facing in many parts of the country. The march was held to urge President Woodrow Wilson to take action on behalf of African Americans and to keep the promises he made during his election. At the time, racial violence and discrimination were rampant, especially in southern states, and many African Americans were being targeted by violent mobs. The parade was also a response to a race riot that had recently occurred in East St. Louis, Illinois, where white mobs had attacked and killed at least 200 African Americans.

The Silent Parade was a peaceful protest, with participants marching silently down Fifth Avenue to mourn the loss of life and demand an end to racial violence. The marchers wore white to symbolize mourning, and women and children marched in the front, while men marched in the back, signifying both their sadness and their resolve to fight for justice. Protesters carried signs with powerful messages like “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” “Mothers, Do Lynchers Go to Heaven?” and “Your Hands Are Full of Blood.” As the marchers passed by, black Boy Scouts handed out flyers to bystanders explaining the struggles African Americans faced.

The march was described as one of the most quiet and orderly demonstrations ever seen in New York, but it was also one of the most powerful. James Weldon Johnson, a leader of the NAACP, wrote about the event, saying, “The streets of New York have witnessed many strange sights, but I judge, never one stranger than this; among the watchers were those with tears in their eyes.” The Silent Parade became a symbol of unity and strength for the African American community and is considered a significant moment in the history of the Civil Rights Movement. It marked a turning point in the struggle for racial justice and helped inspire future protests and actions to fight discrimination and inequality. The march is still remembered today as a bold stand against injustice and a call for change.

important suffragists

Suffragists played a crucial role in securing women's right to vote in the United States, fighting tirelessly for equality and political representation. For decades, they organized marches, petitions, and protests to raise awareness about the injustice of excluding women from the democratic process. The suffrage movement led to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, forever changing the political landscape and advancing the fight for gender equality. The suffragists' bravery and persistence laid the foundation for future movements for women's rights and social justice.

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony was one of the most influential leaders of the women's suffrage movement in the United States. Born in 1820, she was deeply committed to achieving equality for women, particularly in securing their right to vote. Anthony’s work in the suffrage movement began in the 1850s, when she joined forces with fellow activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Together, they formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which aimed to win women the right to vote through constitutional amendments. Anthony's powerful speeches and tireless efforts to lobby lawmakers helped raise national awareness about the injustices women faced in the political system.

One of Anthony’s most famous acts of defiance occurred in 1872 when she was arrested for voting in the presidential election. At the time, women were not allowed to vote, but Anthony cast her ballot

anyway, arguing that the 14th and 15th Amendments, which granted citizenship and voting rights to

"Susan B. Anthony," National Park Service

former slaves, should also apply to women. Her arrest brought significant attention to the cause, and although she was fined, she refused to pay, using the moment to draw attention to the inequality in the legal system. This bold action symbolized her dedication to the cause and showcased her belief that civil disobedience was a powerful tool for social change.

Anthony's contributions to the suffrage movement were critical in securing the passage of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote in 1920. While she did not live to see the amendment become law (she died in 1906), her lifelong dedication and leadership helped lay the groundwork for future victories. Anthony’s relentless work as an organizer, fundraiser, and strategist inspired countless other women to join the suffrage movement, and her legacy continues to inspire gender equality activists today. Her belief in women’s right to vote and her commitment to equality played a central role in transforming the political landscape of the United States.

Learn more about her here:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/susan-b-anthony

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a key figure in the early stages of the women’s suffrage movement and is often credited with laying the intellectual and organizational foundation for the fight for women’s right to vote in the United States. Born in 1815, Stanton was an outspoken advocate for women's rights from a young age. She is best known for organizing the first women's rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, where she presented the Declaration of Sentiments calling for women’s equality in all areas of life, marking the beginning of the organized women’s suffrage movement in the U.S., setting the stage for future campaigns for women’s rights.

Stanton’s work in the suffrage movement was not just about organizing events or speeches; she was also a writer and thinker who shaped the intellectual arguments for women's equality. She believed that the fight for women's suffrage was part of a broader struggle for gender equality, which included women’s rights to property, education, and divorce. Throughout her life, Stanton wrote and spoke about the ways that social, political, and legal systems oppressed women. Her writings, including The

"Elizabeth Cady Stanton," National Park Service

Woman’s Bible and her extensive correspondence with other activists, challenged societal norms and helped shift public opinion about women’s roles in society. Her sharp critique of laws that restricted women’s rights was a crucial part of building the moral and legal case for suffrage.

While Stanton’s approach to suffrage was sometimes controversial, especially in her early years, her leadership and vision were central to the success of the movement. In 1869, she and Susan B. Anthony founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which focused on securing the right to vote through a constitutional amendment. Stanton served as the president of the organization for many years and used her platform to advocate for a wide range of social reforms, from women’s education to labor rights. Although she did not live to see the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, Stanton’s work laid the groundwork for the eventual success of the suffrage movement. Her pioneering efforts, particularly at Seneca Falls, remain one of the most important milestones in the history of women's rights in the United States.

Learn more about her here:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-cady-stanton

Alice Paul

Alice Paul was one of the most influential and radical leaders in the women’s suffrage movement, known for her strategic, bold tactics and unwavering commitment to securing the right to vote for women in the United States. Born in 1885, Paul was inspired by the suffrage activism she witnessed during her studies in England, where she became involved in the more militant wing of the British suffrage movement. After returning to the U.S., Paul joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but she quickly grew frustrated with its conservative approach. In 1916, she founded the National Woman’s Party (NWP), which took a more direct and confrontational stance toward suffrage, marking a shift in the movement’s approach to activism.

One of Paul’s most notable contributions to the suffrage movement was her leadership in organizing the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., just before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The parade, which included over 5,000 women marching down Pennsylvania Avenue, was a highly visible and symbolic act of protest. Despite facing violent attacks from hostile onlookers, Paul and her fellow suffragists persisted, drawing national attention to the movement and its cause.

Paul also pioneered the strategy of picketing the White House, which began in 1917, making the National Woman’s Party the first group ever to picket the White House. These bold tactics were met with hostility and led to the arrest and imprisonment of many suffragists, including Paul herself. However, the picketing brought further visibility to the suffrage movement and pressured the government to take action.

Paul’s unrelenting activism eventually led to the success of the suffrage movement with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which granted women the right to vote. While she was not alone in the fight, her leadership in pushing for direct action and her willingness to take risks were instrumental in the eventual victory. After the passage of the 19th Amendment, Alice Paul continued her work for women's rights, advocating for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and gender equality for the rest of her life. Her radical, unyielding approach to activism and her determination to secure political rights for women left a lasting legacy on the suffrage movement and the broader struggle for gender equality in America.

Learn more about her here:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/alice-paul

"Alice Paul," National Park Service

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott was a pioneering advocate for women's rights and one of the earliest leaders in the American suffrage movement. Born in 1793, Mott was deeply committed to both women's equality and the abolition of slavery, believing that the fight for women's rights was closely tied to the broader struggle for human rights. She was a prominent Quaker, and as part of her faith, she believed in the equality of all people, regardless of gender, race, or social status. Mott’s activism began with her work in the abolitionist movement, where she worked alongside other reformers to challenge slavery, and her commitment to equality naturally extended to the rights of women.

Mott’s most significant contribution to the suffrage movement came in 1848 when she helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention, the first national women's rights convention in the United States. The convention was a historic event, and Mott, alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton, played a key role in drafting the Declaration of Sentiments. This document called for equal rights for women, including the right to vote, and it mirrored the Declaration of Independence, asserting that "all men and women are created equal." The Seneca Falls Convention marked the official beginning of the

women's rights movement in the U.S. and set the stage for decades of suffrage activism. Mott’s clear, moral stance on equality made her one of the most respected leaders of the movement.

Throughout her life, Mott remained a staunch advocate for women’s rights, tirelessly giving speeches and writing articles to promote the cause. She believed that women’s suffrage was just one part of a broader fight for social justice, which included education, property rights, and the right to a fair divorce. Even though she was often overshadowed by more famous suffrage leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mott’s early leadership in the movement was essential to its growth. She was a key figure in shaping the philosophical and moral arguments for women’s equality and helped inspire the next generation of suffragists. Her work paved the way for the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, and her legacy continues to be honored today as a foundational figure in the fight for women’s rights.

Learn more about her here:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/lucretia-mott

"Lucretia Mott" National Park Service

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells was a trailblazing African American journalist, activist, and suffragist who made significant contributions to both the anti-lynching movement and the fight for women's right to vote. Born into slavery in 1862, Wells became a prominent voice against racial violence and injustice in the United States. As a journalist, she used her platform to expose the horrors of lynching, investigating and reporting on lynchings across the South. Her powerful writings and public speeches brought national attention to the brutal treatment of Black Americans, and she became one of the first activists to call for federal anti-lynching legislation. While her work as a journalist was central to her activism, Wells also believed strongly in women's rights and worked tirelessly to secure the right to vote for women, especially Black women, who were often excluded from mainstream suffrage organizations.

Wells’ involvement in the suffrage movement was shaped by her recognition that the fight for women's rights could not be separated from the struggle for racial equality. In the 1890s, she became an active member of the suffrage movement, but she was often confronted with racial discrimination by white suffragists, who did not always include Black women in their efforts. Despite this, Wells refused to be

sidelined. She played a key role in founding the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago in 1913, one of the first suffrage organizations for African American women. The club helped Black women organize for the right to vote and was instrumental in getting them involved in the broader suffrage movement, particularly in Illinois. Wells also worked closely with other prominent suffragists, including Susan B. Anthony and Jane Addams, advocating for the inclusion of Black women in suffrage campaigns.

Ida B. Wells' unique position as both a Black woman and an outspoken suffragist allowed her to challenge the racial and gender divides within the suffrage movement. She was a vocal critic of the exclusion of Black women from the suffrage process and was committed to ensuring that both Black and white women gained the right to vote. Wells' work, both as a journalist and as a suffrage leader, helped expand the suffrage movement’s focus to include racial justice and equality. Her determination and resilience in the face of both racial and gendered discrimination left a lasting legacy on the suffrage movement and on the broader civil rights movement. Wells' contributions paved the way for future generations of activists and highlighted the intersection of race and gender in the fight for equality.

Learn more about her here:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-b-wells-barnett

"Ida B. Wells," National Park Service